Naming works is usually a struggle for me, and this one in particular. Through the making of the work I sought to acknowledge the forgotten people at the periphery of official history who had been on the island before me, but there were so many it was difficult to encapsulate them within a few words. One trace of existence which had particularly haunted me was the gravestone of a little boy, the infant son of Superintendent Samuel Lapham, who had lived on the island during the second convict era. I unearthed no other evidence of this child's existence and found it difficult to comprehend that he and his mother were in residence in what must have been a very challenging environment. Charles Henry Lapham died June 28, 1848. The footstone of his grave reads "One Year and One Day", notating his age at death.

Artist Statement:

One Year and One Day

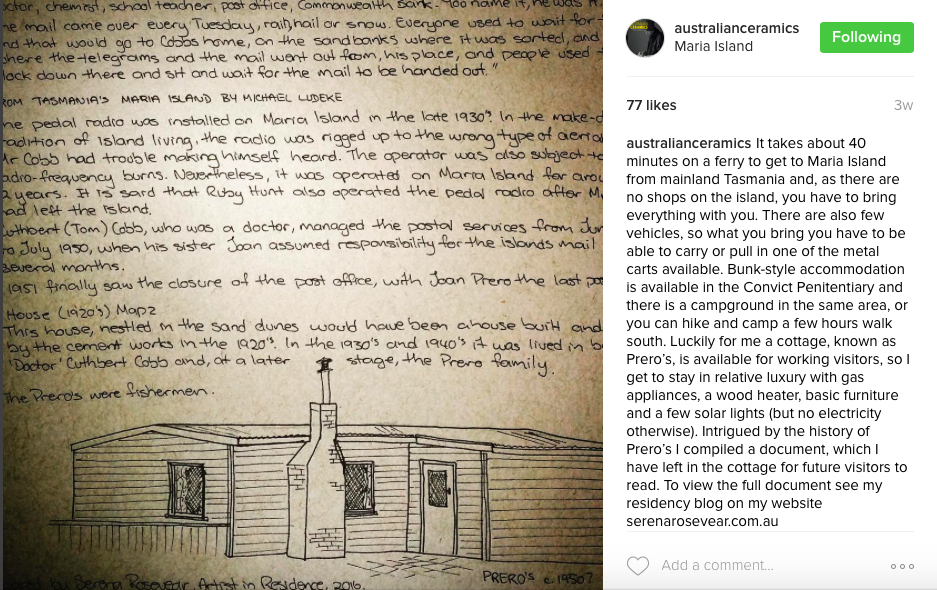

This place. I’ve learnt to read it. I’ve traced the steps of those before me, touched the surfaces they created, devoured their words, burnt their saplings. I’ve reinterpreted the interpretation, hunted out evidence that spoke more truthfully to me, become distracted by traces that speak of small stories at the periphery of official history. I’ve found kindred sprits in those long gone: masters of make-do. And so, with not much more than my hands and the resources of the island, I toil away at repetitive labour seeking to pay homage; to their ingenuity, their resilience, their presence.

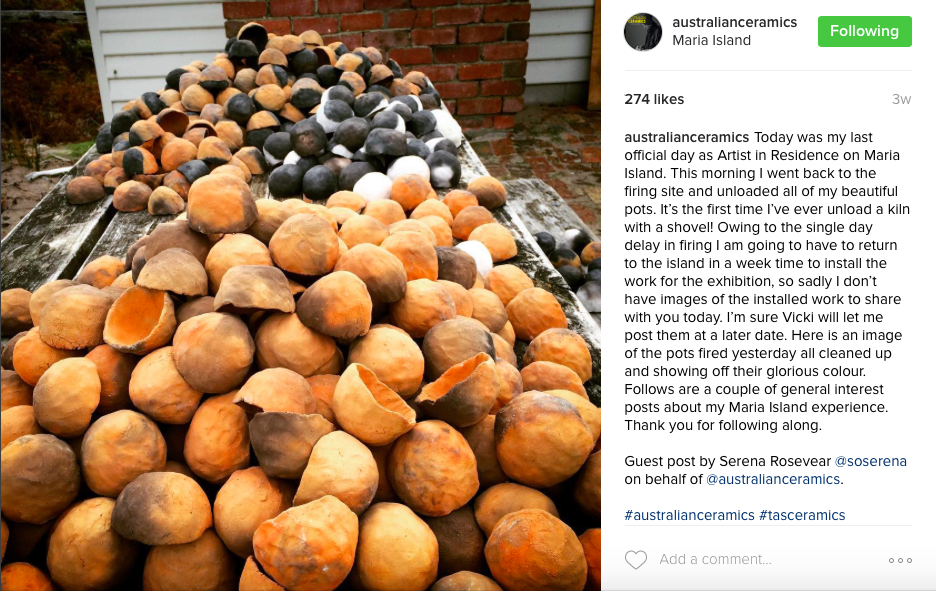

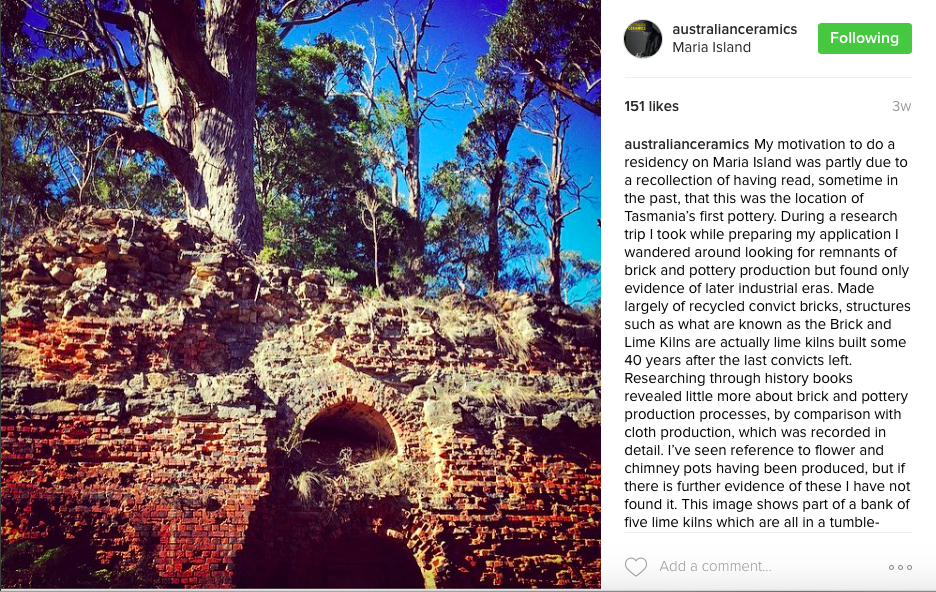

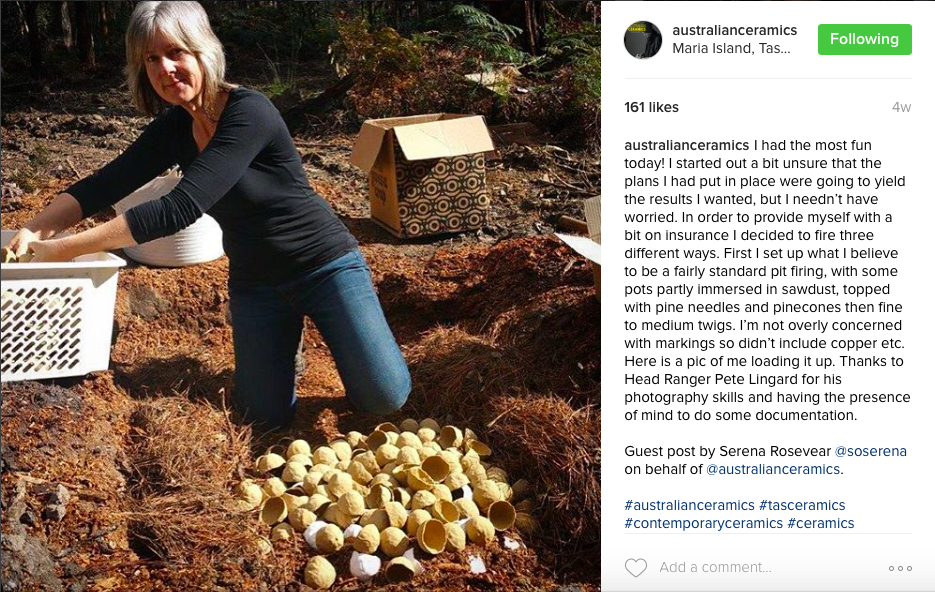

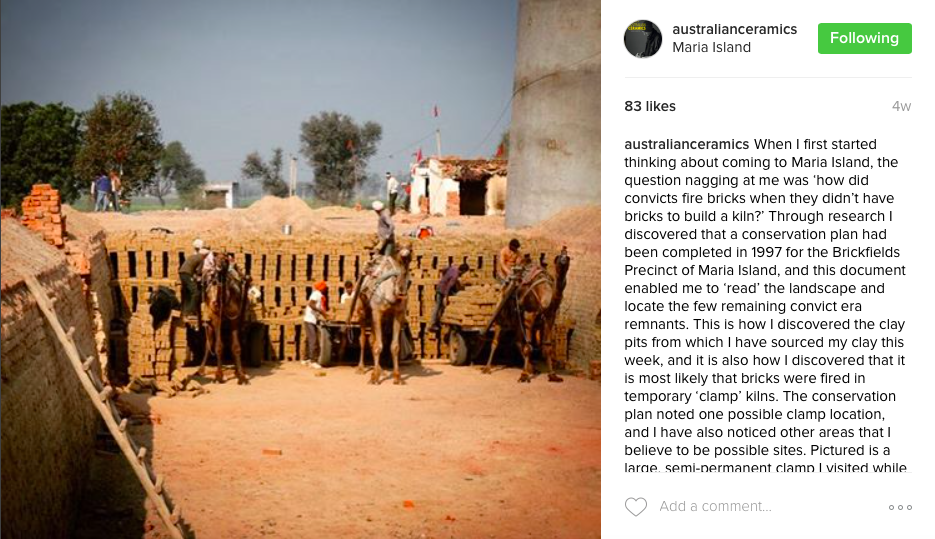

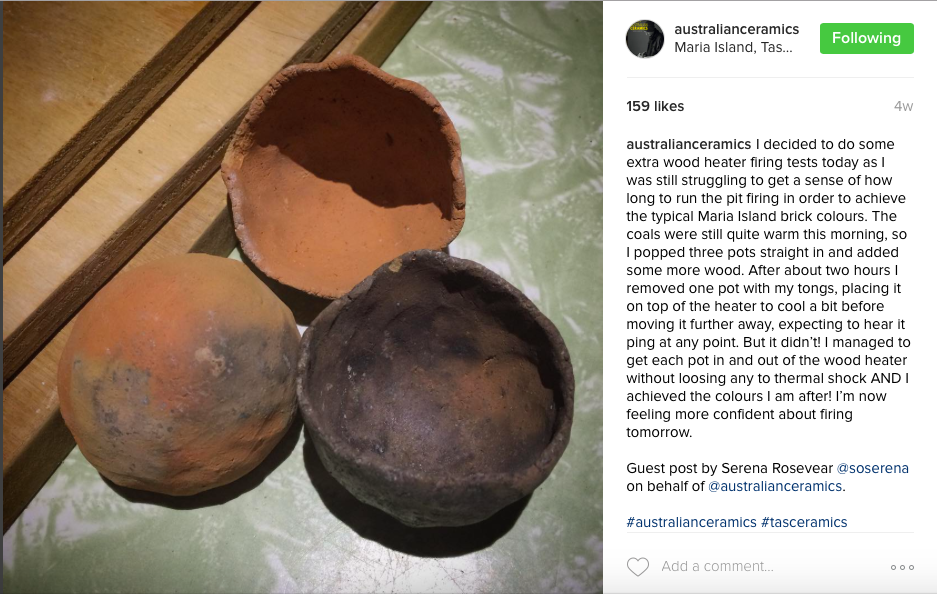

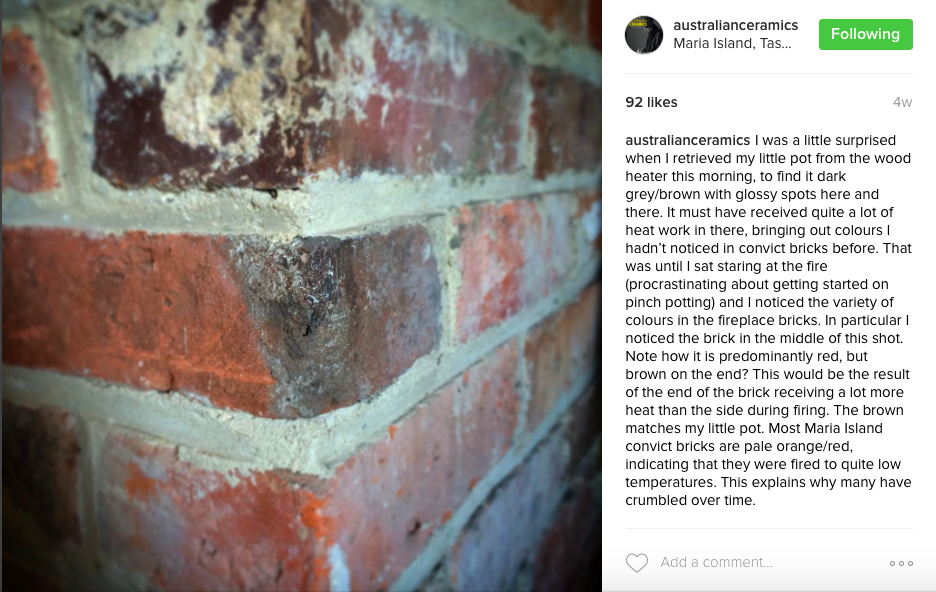

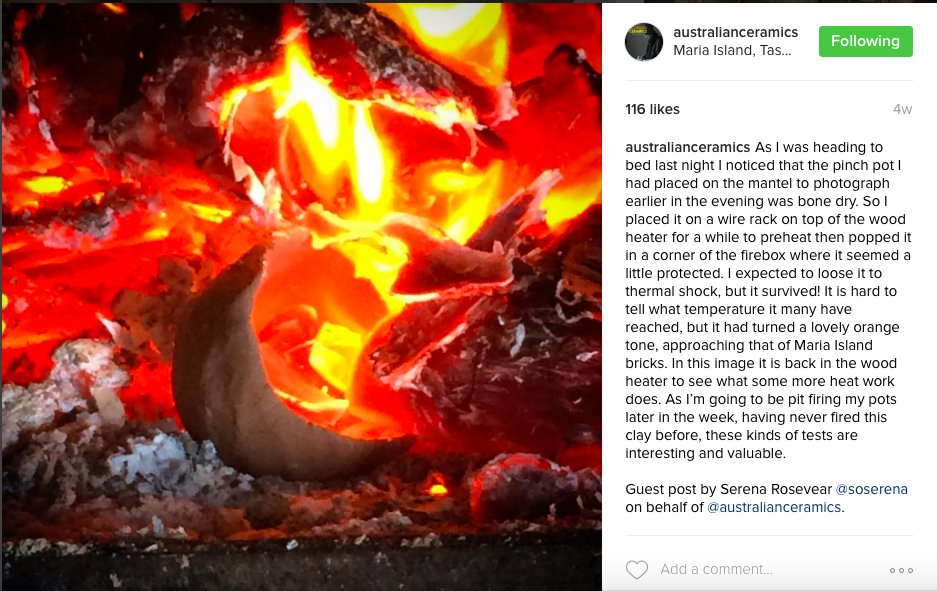

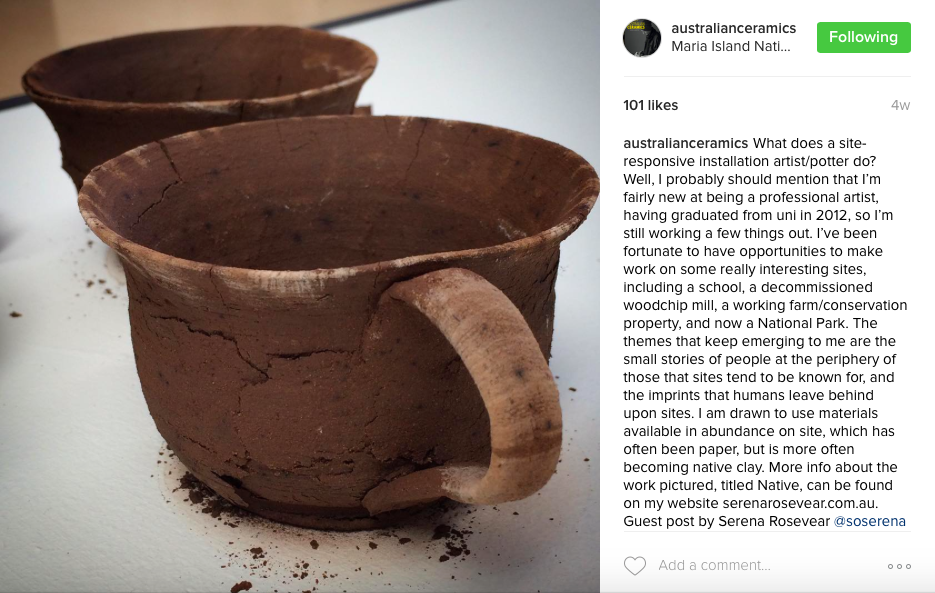

The work consists of over 1200 clay pots installed upon a mesh table found on the island. Though the numbers are not accurate (I found it impossible to derive an actual figure) the different colours seek to represent the people who occupied the island in seperate eras. The brick-coloured pots represent the convicts, the white pots residents of the industrial eras, and the various shades of grey those such as farmers, aboriginals, whalers and government employees. The clay for the brick-coloured pots was sourced from within the pits used by convicts and these were fired upon the island using a rudimentary firing method not dissimilar to that used by convicts to fire bricks.